Moral Reckonings: Student Reflections on The Holocaust Exhibition and The Sunflower

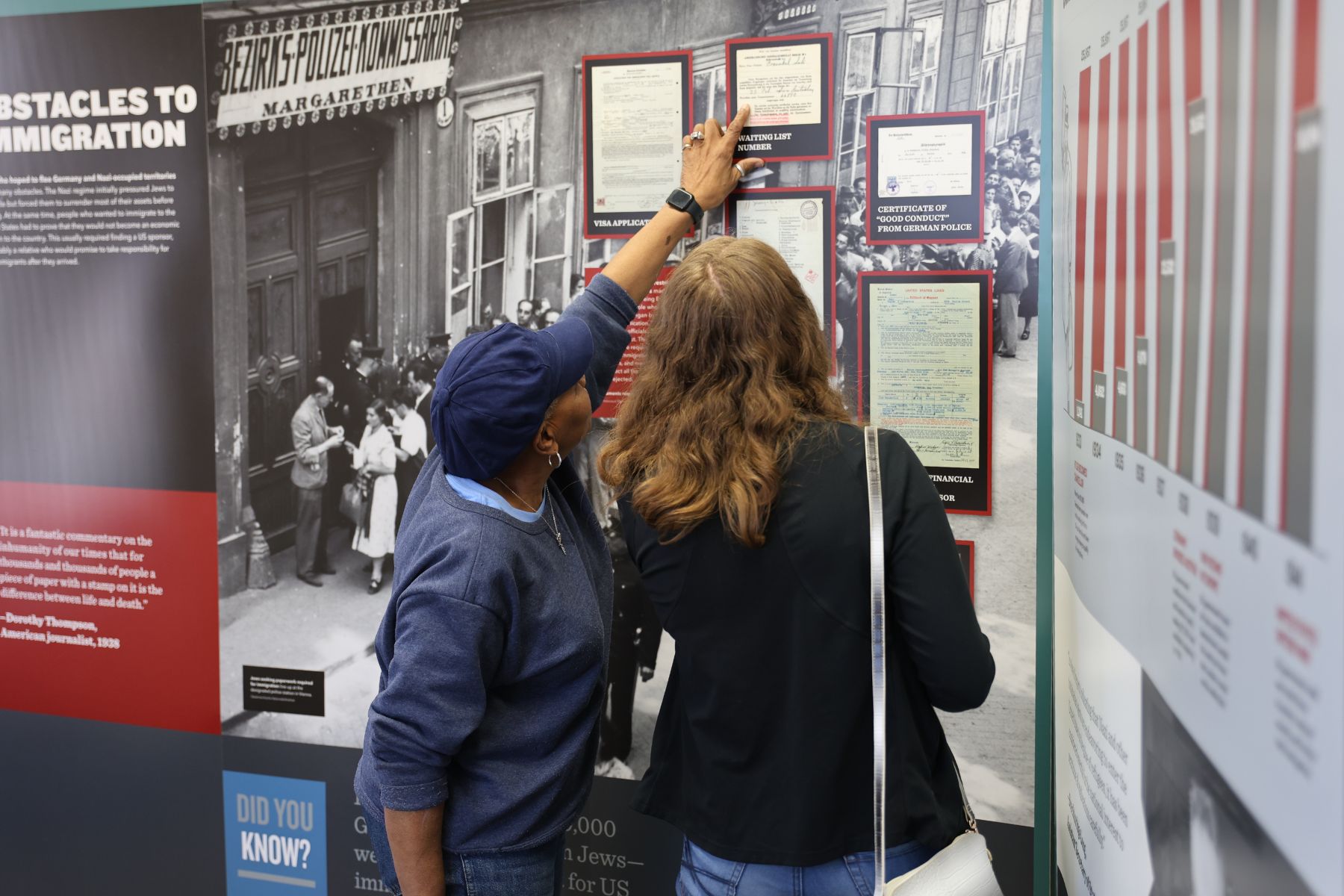

The national touring exhibition “Americans and the Holocaust” was on display at the Carnegie Free Library in Beaver Falls from March 17 to April 28, 2025. This visiting exhibit was made possible through the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the American Library Association.

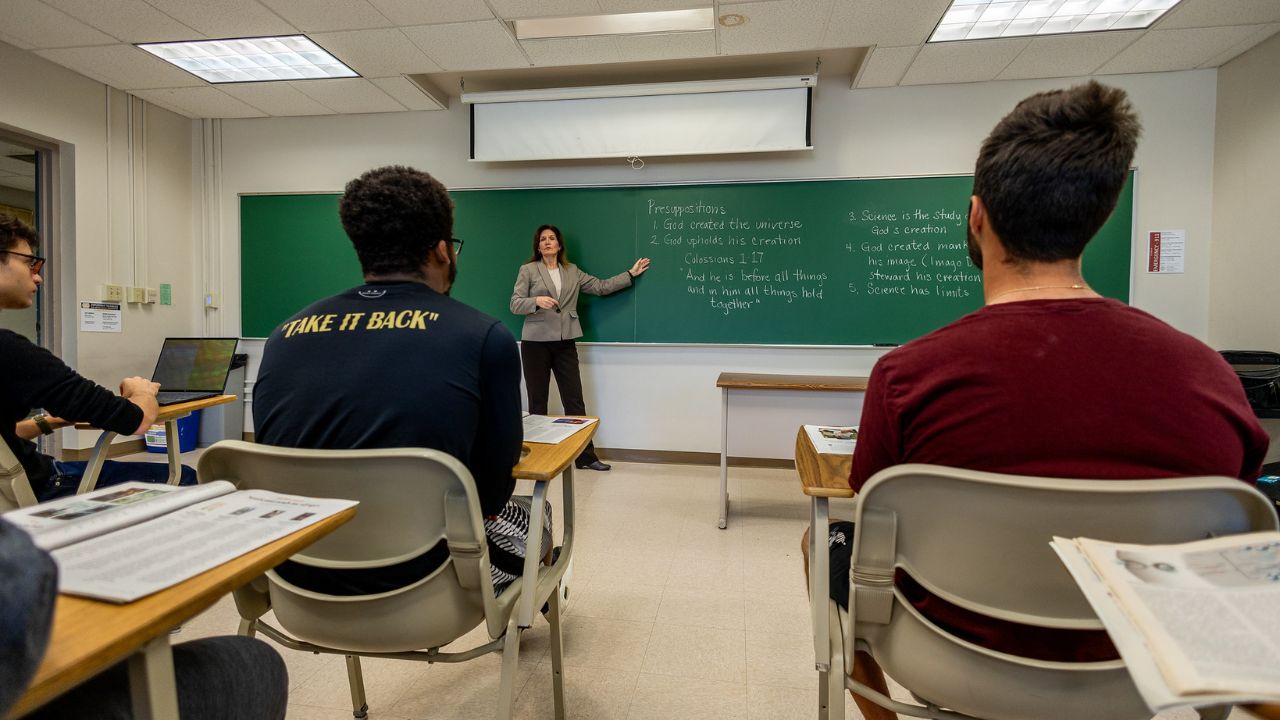

Geneva students were encouraged to visit the exhibition in their own time and as part of some classes, most notably through Humanities 303: Perspectives: Modernity, Post-Modernity, & Virtual Culture.

The Humanities 303 curriculum adjusted to include a visit to the “Americans and the Holocaust” exhibition in conjunction with reading the course text The Sunflower by Simon Wiesenthal. Students were prompted to reflect on both experiences: “After visiting the Holocaust exhibit at the Carnegie Library in Beaver Falls, what is one image, photograph, detail, quote, etc. from the exhibit that interested or captivated you? Write a reflection that connects what you experienced at the exhibit and what you read in the Sunflower.”

Students in the spring 2025 offering of Humanities 303 share portions of their reflections below.

Abigail Martin ‘26

I am grateful for the experience to visit the Holocaust Exhibit. I took a genocide course in high school, and I learned things at the exhibit that I never knew about. I think the exhibit was very well put together, and I hope others get the opportunity to learn from it.

Emma Kline ‘27

One of my favorite pieces from the Holocaust exhibit comes from the panel titled “Should America go to War?”, as I appreciated getting to see Dr. Seuss’ political cartoons, and the way he satirically represented the ideals of the isolationist movement. I believe that it is understandable to see how many in the United States during the early parts of the war would have been drawn in by the idea of isolationism. Balancing national security with fighting for a cause that had (not quite yet) reached American shores is a difficult call to make. However, this panel helped me to reflect once more on the complicated question of when the time has come to get involved. As Dr. Seuss so craftily put it, “and the Wolf chewed up the children and spit out their bones… But these were Foreign Children, and it really didn’t matter.” So, when does it matter? This is the question we need to ask ourselves, and keep asking ourselves, because unfortunately we are happy to put “America first” (another panel I find incredibly thought-provoking) until it is too late.

I think of Wiesenthal’s experience of “the day without the Jews”, and the fact that the violence against Jewish students was only perpetrated by about twenty percent of the student body. How did they get away with this? Because the majority of the students did nothing. Wiesenthal explains that “The great mass of the students were unconcerned about the Jews or indeed about order and justice. They were not willing to expose themselves, they lacked willpower, they were wrapped up in their own problems, completely indifferent to the fate of Jewish students” (Wiesenthal, 19). Wiesenthal’s experiences before, during, and after the Holocaust (especially when he visits Karl’s mother) reveal the horrors that can occur when people stand silently by and do nothing in the face of evil. I understand the importance of putting America first, I really do; I just do not think I will ever be able to reconcile putting our country before the lives of millions of innocents. This is one of the biggest things I took away from the exhibit, because even though it is talking about something that happened 85 years ago, these questions are still every bit as relevant today.

Andrew Shenk ‘26

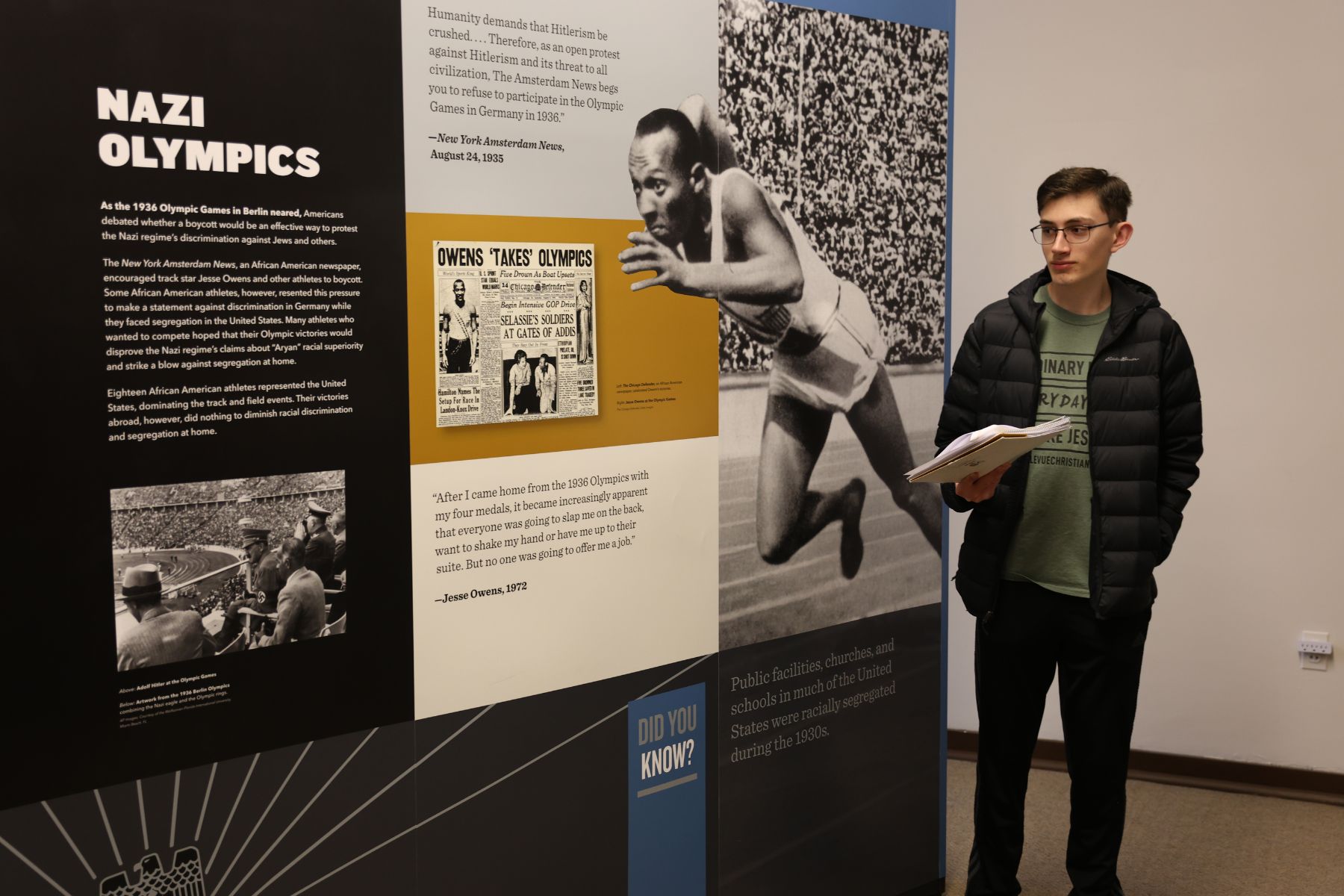

While at the Holocaust exhibit at the Carnegie in Beaver Falls, I was captivated by the “Nazi Olympics” section, which detailed the racial tensions present at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. Fascinatingly, there was heated pressure regarding African-American involvement in the Olympics, as newspapers encouraged African-American athletes to abstain from participation. Athlete Jesse Owens, however, chose to compete in order to disprove the idea of Aryan superiority, which was prevalent in Nazi Germany as well as the United States. Therefore, Jesse’s motivations were rooted in the hope of eradicating racial discrimination and segregation, which was still a significant problem in the United States.

A quote that stuck to me reads as follows, “After I [Jesse Owens] came home from the 1936 Olympics with my four medals, it became increasingly apparent that everyone was going to slap me on the back, want to shake my hand or have me up to their suite. But no one was going to offer me a job.” (Jesse Owens 1972). Such a quote represents the significant cognitive dissonance of racial discrimination, in which the recognition of humanity is rejected despite insurmountable evidence. Such dehumanization reminds me of The Sunflower, in which Karl was indoctrinated to believe that, “They are not our people. The Jew is not a human being!... And when you shoot one of them it is not the same thing as shooting one of us…” (Wiesenthal 49). Ultimately, the grave mistreatment of Jews and Africans alike was only possible through dehumanization, in which both America and Nazi Germany were guilty. Therefore, we must learn from the homicides and injustices of the past, recognizing that grave evil is still made possible through the diminishing of the Imago Dei.

Rowan Dennis ‘26

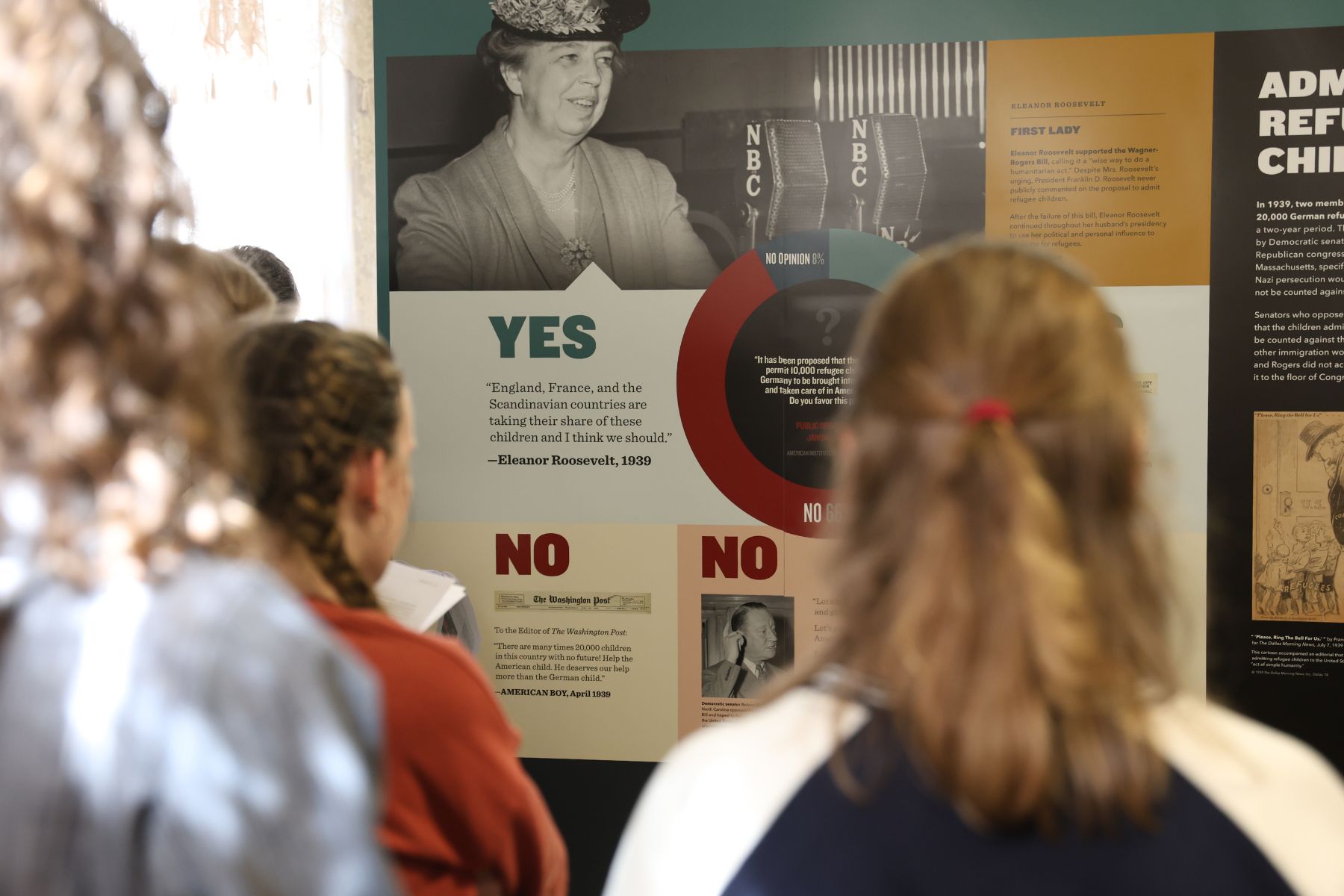

After visiting the Holocaust exhibit at the Carnegie Library in Beaver Falls, countless black-and-white images of violence and death are burned into my mind and weigh heavy on my heart. But maybe even more than this, the responses of Americans at the time to the horrific tragedies that occurred leave me greatly disturbed. In November of 1938, public opinion polls were conducted several weeks after the Kristallnacht attacks. Upon being asked this question: “Do you approve or disapprove of the Nazi treatment of Jews in Germany?” 94% respondents disapproved while 6% approved, and 71% answered the follow up question: “Should we allow a larger number of Jewish exiles from Germany to come to the United States to live?” saying “no,” whereas 21% said yes and 8% kept silent (or “no opinion”). My mind flashed back to the “Sunflower,” where Simon wrestled with the question of whether or not God was present in all of this suffering. He, along with countless others, had been convinced that “God was on leave.” I can only imagine that the responses of the Americans furthered this perceived reality that God was on leave. A seemingly “Christian” nation stood by and watched the killing of millions of innocent people, disapproving and maybe even feeling some sort of inward tension of disgust or injustice, yet sitting under a shadow of fear to move or act. Conviction without action is dead. A land that had claimed justice and freedom washed its hands of any blood that might soil such comfortable ideas. I cannot pretend, in all of my comfort and removal from this historic period that I would have been any braver or that I know what the correct response of my country should have been. Sometimes I wonder if this question is even a productive one. Yet I can only imagine the distance from God Simon felt as the “home of the free and the brave” closed itself off to Jewish exiles from Germany. As my eyes traced these words and gazed at the colorful pi charts on the displays, I better understood the belief that God was no longer present. Not in the negative responses or those who protested against the Jews and the possibility of their coming to America, but in those who chose to stay neutral. I am not saying that these negative responses were correct, yet I feel as though silence is more violent than a “yes” or a “no.” My mind recalls Revelation 3:16, which says, “So, because you are lukewarm and not hot or cold, I will spit you out of my mouth.”

Elliana Zwatty ‘27

After visiting the Holocaust exhibit at the Carnegie Library in Beaver Falls, a quote that continued to stand out to me was Dwight D. Eisenhower’s response after visiting the concentration camps. Eisenhower stated that “the things I saw beggar description... The visual evidence and the verbal testimony of starvation, cruelty, and bestiality were so overpowering as to leave me a bit sick... I made the visit deliberately, in order to be in a position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to change these allegations merely to ‘propaganda’.” Eisenhower’s response to the atrocities witnessed reminded me of the Sunflower and the issue of silence that was brought up in the memoire. After the Holocaust, many survivors were scared to speak up about the horrors that they had witnessed, so they instead chose to stay silent, which in turn allowed the perpetrators to live their lives free from the consequences of their actions. This silence also then made it easier for others to discredit and even forget the experiences of the victims in the Holocaust. Simon Wiesenthal and Eisenhower’s choice to stand up for the truth and provide first-hand evidence and account of the horrors of the Holocaust forced society to remember the people who had lost their lives in the Holocaust. Along with this, Wiesenthal’s push towards finding the perpetrators from the Holocaust and bringing them to justice further forced society to not forget the horrors of the Holocaust, allowing them to be swept under the rug by silence and forgetfulness.

Andrew Whaples ‘26

Not too long ago, my aunt and I, the family genealogists, determined that a portion of our German heritage was actually comprised of enough DNA to be classified as independently Jewish. In response to both that and a writing assignment in community college, I wrote the following Cinquain: Erase—Criminalized—Innocent, Punishment—Tormented gravely worse than game—Escape. It is dedicated to a Polish Jew named Abraham Bergman, a living Holocaust survivor, making him a contemporary with Simon Wiesenthal. Both of these personal connections with Holocaust history heightened my senses during the recent trip to the Holocaust Exhibit, where I took note of a particular picture on the background of a frame board. It’s a black and white image of a group of Dutch Jews being boarded onto the Deutsche Reichsbahn for transport to Westerbork Camp, and then dispersion to one of a number of the “final solution” camps. Within the image I noticed the smiles and dare I say joviality of the people, which made me to recall Simon’s depiction of the Technical School where he had endured his schooling, reviling and dehumanizing slander, along with the confession of the SS man. For both images, places of happiness and joy became places of utmost peril and destruction. It also recalled an old saying white Americans had hurled at my noticeably Jewish Uroma [slang for Urgroßmutter, meaning Great-Grandmother] Dorothy Fischbach, which went: “You can fisch the Bach’s but they just won’t go”. Wiesenthal utilizes the image of the sunflower, and I shall use the image of uprooted tulips, edelweisses and knapweed to symbolize the removal of Jews from various countries and places, dare I use the black-eyed Susan for my Uroma; depictions of God’s image tossed aside as though an uprooted tulip.

Reese Miller ‘25

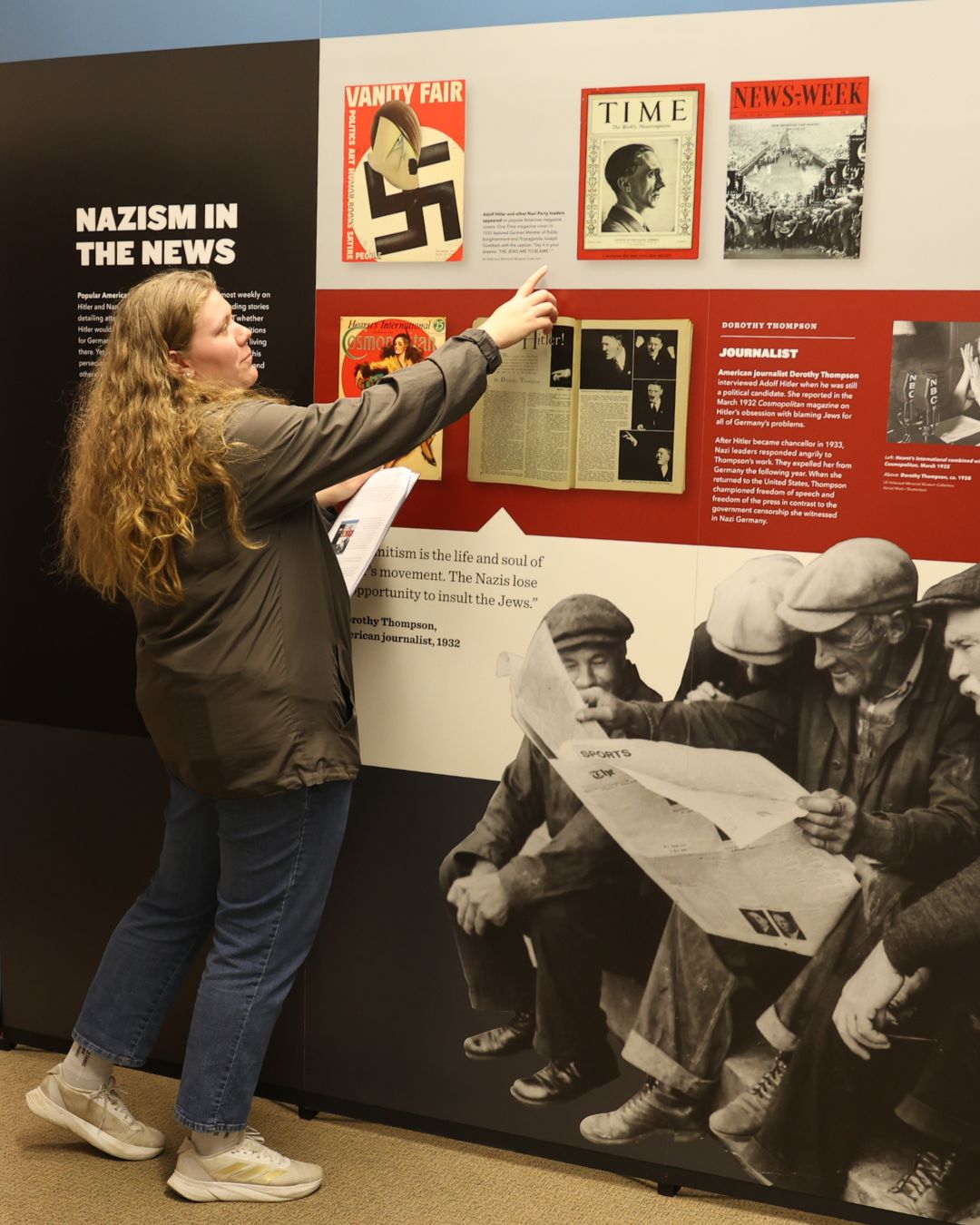

Of particular interest to me was the portions of the Holocaust exhibit dealing with the war propaganda and marketing the ideas of war to the public. These parts of the exhibit are the “Why We Fight” and “Should America Go to War?” panels.

The “Should America Go to War?” panel is especially potent on the mind right now as conflicts in Asia and Europe prompt questions of whether we should be isolated, involved, or engaged as regards the conflicts. As many agree, the war against Germany was indeed a just war, and so in looking into the specific arguments for war we find why we should go to war or not. It’s not a light decision. The isolationists argued for the lives of our soldiers as sons, and said that the situation in Europe was its own fault. Interventionists argued for the lives of the Jewish people and Americans as they portrayed Germany as growing to threaten both.

In the end, the most telling arguments given to the American people in the “Why We Fight” panel appeal to Christian Faith, the American Constitution, American patriotism against Nazi threat, economic threat, and threats to children. These reveal the heart of the loyalties of the Americans. They also show no signs of Jewish protectionism. The horror of what really occurred in Nazi Germany was hard to comprehend by Americans, and no one would have been imagining the kinds of torture which were inflicted on Jews as detailed in the Sunflower. Information is hard to integrate into the public of such stark evil that many would not believe it, as some of the statistics in the panels revealed. Information was also hard to gather, as illustrated in the Sunflower few thought to speak out or speak into the Jewish communities in trouble.

Wiesenthal, Simon. The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness. New York: Schocken Books, 1998.

Opinions expressed in the Geneva Blog are those of its contributors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or official position of the College. The Geneva Blog is a place for faculty and contributing writers to express points of view, academic insights, and contribute to national conversations to spark thought, conversation, and the pursuit of truth, in line with our philosophy as a Christian, liberal arts institution.

Jul 22, 2025Humanities and Liberal ArtsRelated Blog Posts

Request Information

Learn more about Geneva College.

Have questions? Call us at 724-847-6505.

Online Course Login

Online Course Login